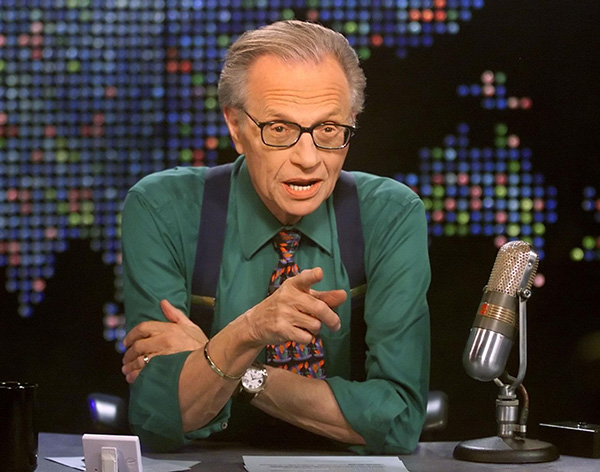

The legendary talk-show host, Larry King, died at age 87 on January 23, 2021, after…

What did the Supreme Court Do when they Struck Down DOMA?

(This article is written solely for informational purposes for those interested in the law. If you believe you may have a personal claim under the decision in Windsor, contact an attorney with the proper knowledge of federal and constitutional law.)

Intro

First, it is simply incorrect to say that the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) “struck down” the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA). SCOTUS via their decision in US v. Windsor last summer struck down the portion of Section 3 of the Act that defines “marriage” and “spouse” for a number of federal government purposes to only be created by relationships between a male and female. To start off, let’s talk about what brought the case about.

In 2007, Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer were legally married in Ontario, Canada. They were at the time residents of New York State and lived out the length of their marriage in New York. Spyer had quite a bit of money, and upon her death in 2009, her will granted her entire estate to Windsor. Edith then attempted to claim the federal estate tax exemption so that the money she inherited from her dead spouse would not be taxed. Absent DOMA, Windsor could have done so because the United States generally recognizes Canadian marriages. However, DOMA was still in force at the time, costing Windsor over $360,000.00 in taxes. Thus came the court case.

The (Heavily Abridged) Decision

Writing for a 5-4 majority opinion, Justice Kennedy wrote that “DOMA’s principal effect is to identify a subset of state-sanctioned marriages and make them unequal. The principal purpose is to impose inequality, not for other reasons like governmental efficiency.” For these reasons and others, the majority ruled that Section 3 of DOMA Violated the Due Process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The 5th Am., among other things, guarantees that the federal government (that part is important) shall not deprive anyone of “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” To put it simply, the majority ruled that the federal government, via DOMA and its imposition of inequality between heterosexual and homosexual marriages, was depriving Windsor of her property (i.e. estate tax exemption of $360k). Such inequality, according to SCOTUS, was a violation of the 5th Amendment, and warranted the overruling of Section 3 of DOMA.

What the Court did NOT do.

The big thing the Court did not do is they did not lend further legitimacy to non-heterosexual marriage in any other context than DOMA and the actions of the federal government. While parts of the 5th Amendment have been incorporated to the states (like double jeopardy and the prohibition against being forced to testify against yourself) by previous court decisions, the due process clause of the 5th Amendment only applies to the federal government. This means the Court did not force states who currently do not allow same-sex marriages to do so, nor did they mandate that those states recognize same-sex marriages from other states or countries. In the companion decision Hollingsworth v. Perry, SCOTUS ruled that the challengers to a California Supreme Court decision that struck down a California Constitutional Amendment that would have banned same-sex marriage did not have standing to challenge the earlier state court decision, and that SCOTUS could not therefore hear their substantive arguments. Again put simply, SCOTUS punted the question of whether or not allowing same sex marriage was prohibited by the 14th Amendment, and allowed the status quo to continue in California.

Questions Left Unanswered

While proponents of the decision in Windsor generally hail the decision as a victory, but sides grumble that the Court distinctly refused to answer some blaring questions starring them right in the face. The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, that apply to the federal and state governments respectively, both have due process clauses. In fact, their language is almost identical, which was no doubt the intention of the 14th Amendment’s drafters. If discrimination against same-sex marriage is forbidden by the 5th, then how is it not prohibited by the 14th also? In his dissent, Justice Scalia points out what he sees as an absurd legal fiction created by the majority, writing “As far as this Court is concerned, no one should be fooled; it is just a matter of listening and waiting for the other shoe… By formally declaring anyone opposed to same-sex marriage an enemy of human decency, the majority arms well every challenger to a state law restricting marriage to its traditional definition.” Both sides of the argument clearly see the gap in the majority’s reasoning, opponents arguing the majority lacked reason, proponents arguing the Court did not follow through with their own logic.

Proponents also point out that Article IV of the Constitution mandates that the states give “full faith and credit… to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other state.” Marriages are judicial acts supported by state legislation. How then can same sex marriages not be allowed recognition in no same sex marriage states? SCOTUS refused to force the states’ hands in the civil rights context also, deciding ultimately to strike down anti-interracial marriage laws themselves rather than force those states to recognize marriages from other states. Then again, these are VERY different social issues, and it is hard to imagine that the drafters of Article IV, the 5th Amendment, or the 14th Amendment had same-sex marriage in mind when the they all were written. On the other hand, Justice Marshal famously wrote “We must never forget that it is a Constitution we are expounding,” pointing out that the United States Constitution is a living document that in his view must be interpreted with the times. Originalist Justices Scalia and Thomas would no doubt disagree.

Conclusion

US v. Windsor was a landmark decision any way you look at it. Then again, Dread Scott and Lochner, the decisions upholding the Fugitive Slave Act and forbidding reasonable labor protections respectively, were also landmark decisions. This article was not intended to justify nor condemn the decision in Windsor, but to clarify what the Court actually DID, and what they did NOT do. I hope that goal was accomplished.